Witches known as skinwalkers can alter their shapes at

will to assume the characteristics of certain animals are in religion and

cultural lore of Southwestern tribes. They are not werewolves and other types of weres, but like I said, wtiches.

In the American Southwest, the Navajo, Hopi, Utes, and other

tribes each have their own version of the skinwalker story, but they all end up

to the same thing--a malevolent

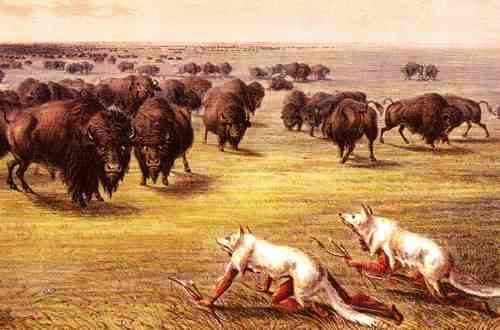

witch capable of transforming itself into a wolf, coyote, bear, bird, or any

other animal. The witch might wear the hide or skin of the animal identity it

wants to assume, and when the transformation is complete, the witch inherits

the speed, strength, or cunning of the animal whose shape he/she has taken.

Navajo skinwalkers use mind control, make their victims hurt

themselves and even end their

lives. They are considered powerful, able to run faster than a car and jump

mesa cliffs without any effort at all. No faster than a speeding bullet and

able to leap tall buildings like Superman, but not much lesser.

For the Navajo and other tribes of the southwest, the tales

of skinwalkers are not mere legend. There’s a Nevada

attorney, Michael Stuhff, one of the few lawyers in the history of American

jurisprudence to file legal papers against a Navajo witch. He often represents

Native Americans in his practice and understands Indian law. He knows and

respects tribal religious beliefs.

As a young attorney in the mid-70s, Stuhff worked in a legal

aid program based near Genado,

Arizona,

many clients being Navajo. He confronted a witch in a dispute over child

custody. His client was a Navajo woman who lived on the reservation with her

son. She wanted full custody rights and back child support payments from her

estranged husband, an Apache man. At one point, the husband got permission to

take the son out for an evening, but didn't return the boy until the next day.

The son later told his mother what had happened. He had spent the night with

his father and a "medicine man." They built a fire atop a cliff and,

for many hours, the medicine man performed ceremonies, songs, and incantations

around the fire. At dawn, they went to some woods by a cemetery and dug a hole.

The medicine man placed two dolls in the hole, one dark and the other made of

light wood. The dolls were meant to be the mother and her lawyer. Sruhff

didn’t know how to approach this, so he consulted a Navajo professor at a

nearby community college.

The professor told him it sounded like a powerful and

serious ceremony of type, meant for the lawyer to end up buried in the

graveyard for real. He also said a witch could only perform this type of

ceremony only four times in his life, because if he tries it more than that,

the curse would come back on the witch himself. Also, if the intended victim

discovered about it, then

the

curse would come back onto the person who had requested it.

Stuhff filed court papers that requested an injunction

against the husband and the unknown medicine man, whom he described in the

court documents as "John Doe, A Witch,” to let the husband know he know

what he and the witch had done. He described the alleged ceremony in detail.

This upset the opposing attorney by the motion, as did the

husband and the presiding judge. The opposing lawyer argued to the court that

the medicine man had performed "a blessing way ceremony," not a

curse. But Stuhff knew that the judge, who was a Navajo, would be able to

distinguish between a blessing ceremony, which takes place in Navajo hogans,

and a darker ceremony involving lookalike dolls that took place in the woods

near a cemetery. Which he did. Before the judge ruled though, Stuhff requested

a recess so that the significance of his legal motion could sink in. The next

day, the husband agreed to grant total custody to the mother and pay all back

child support.

Stuhff took it as serious as the husband did, because he

learned that sometimes witches will do things themselves to assist the

supernatural, and he knew what that might mean.

Whether or not Stuhff believed that witches have

supernatural powers, he acknowledged the Navajos did. Certain communities on

the reservation had reputations as witchcraft strongholds and the lawyer wasn’t

certain that the witch he faced was a skinwalker or not. "Not all witches

are skinwalkers," he had said, "but all skinwalkers are witches.

Skinwalkers are at the top, a witch's witch. Skinwalkers

are purely evil in intent. That they do all sorts of terrible things---make

people sick and they commit murders. They are also grave robbers and

necrophiliacs. Greedy and evil, to become a skinwalker, they must kill a

sibling or other relative. They supposedly can turn into were-animals and

travel by supernatural means.

Skinwalkers possess knowledge of medicine, medicine both

practical (heal the sick) and spiritual (maintain harmony). The flip side of

the skinwalker coin is the power of tribal medicine men. Among the Navajo,

medicine men train over a period of many years to become full- fledged

practitioners in the mystical rituals of the Dine' (Navajo) people.

But there is a dark side to the learning of the medicine

men. Witches follow some of the same training and obtain similar knowledge as

their more benevolent colleagues. But they supplement this with their pursuit

of the dark arts. By Navajo law, a known witch has forfeited its status as a

human and can be killed at will.

Witchcraft was always an accepted, if not widely

acknowledged part of Navajo culture. The killing of witches were historically

accepted among the Navajo as it was among the Europeans." At oe point in

history, thre was the Navajo Witch Purge of 1878. More than 40 Navajo witches

were killed or "purged" by tribe members because the Navajo had

endured a horrendous forced march at the hands of the U.S.

Army in which hundreds were starved, murdered, or left to die. The Navajo were

confined to a bleak reservation that left them destitute and starving at the

end of the march. They assumed that witches might be responsible for their

plight. They retaliated by purging their ranks of suspected witches. Tribe

members reportedly found a collection of witch artifacts wrapped in a copy of

the Treaty of 1868 and "buried in the belly of a dead person."

In the Navajo world, there are as many words for the various

forms of witchcraft as there are words for various kinds of snow among the

Eskimos. If the woman thought a man was adan'ti, she thought he had the power

of sorcery to convert himself into animal form, to fly, or become invisible.

Few Navajo want to cross paths with naagloshii (or yee

naaldooshi), otherwise known as a skinwalker. The cautious Navajo will not

speak openly about skinwalkers, especially with strangers, because to do so

might invite the attention of an evil witch. After all, a stranger who asks

questions about skinwalkers just might be one himself, looking for his next

victim.

In the legends, it is said they curse people and cause great

suffering and death. At night, their eyes glow red like hot coals. It is said

that if you see the face of a Naagloshii, they have to kill you. If you see one

and know who it is, they will die. If you see them and you don't know them,

they have to kill you to keep you from finding out who they are. They use a

mixture that some call corpse powder, which they blow into your face. Your

tongue turns black and you go into convulsions and you eventually die. They are

known to use evil spirits in their ceremonies. The Dine' have learned ways to

protect themselves against this evil, always keeping on guard."

Although skinwalkers are generally believed to prey only on

Native Americans, there are recent reports from non-Indians claiming they had

encountered skinwalkers while driving on or near tribal lands. One New Mexico

Highway Patrol officer told us that while patrolling a stretch of highway south

of Gallup, New Mexico, he had had two separate encounters with a ghastly

creature that seemingly attached itself to the door of his vehicle. During the

first encounter, the veteran law enforcement officer said the unearthly being

appeared to be wearing a ghostly mask as it kept pace with his patrol car. To

his horror, he realized that the ghoulish specter wasn't attached to his door

after all. Instead, it ran alongside his vehicle as he roared at high rate of

speed down the highway. The officer said he had a nearly identical experience

in the same area a few days later. He was shaken to his core by these

encounters, but didn't realize that he would soon get some confirmation that

what he had seen was real. While having coffee with a fellow highway patrolman

not long after the second incident, the cop cautiously described his twin

experiences. To his amazement, the second officer admitted having his own

encounter with a white-masked ghoul, a being that appeared out of nowhere and

then somehow kept pace with his cruiser as he sped across the desert. The first

officer told us that he still patrols the same stretch of highway, but is

petrified every time he enters the area.

Once Caucasian family still speaks in hushed tones about its

encounter with a skinwalker, even though it happened in 1983. As they

drove at night along Route 163 through the Navajo Reservation, the family

felt that someone was following them. As their truck slowed down to round a

sharp bend, the atmosphere changed, and time itself seemed to slow down. That's

when something leaped out of a ditch.

"It was black and hairy and was eye level with the

cab," one of the witnesses recalled. "Whatever this thing was, it

wore a man's clothes. It had on a white and blue checked shirt and long pants.

Its arms were raised over its head, almost touching the top of the cab. It

looked like a hairy man or a hairy animal in man's clothing, but it didn't look

like an ape or anything like that. Its eyes were yellow and its mouth was

open."

Days later, the family awoke to the sounds of loud drumming at their home in Flagstaff. They peered out their windows and saw dark forms of three men outside their fence, trying to climb the fence to enter the yard and inexplicably unable to cross onto the property. Frustrated by their failed entry, the men chanted as the terrified family huddled inside the house.

Strange about this was if skinwalkers, why not assume a shape of a bird and fly over the fence? No mention either of police called. One family member said she called a Navajo friend who walked through the house and said they were skinwalkers, that the intrusion failed because something protected the family. She admittd that it was all highly unusual since skinwalkers rarely bother non-Indians and performed a blessing ceremony.

2 comments:

Cool blog--I love these interesting articles.

Glad you enjoy them, K.R.

Post a Comment